It often begins with a pause. A woman hesitates to name the fear she carries at home; a man struggles to articulate the pressure to be in control. Before speech, the body tells the story: a flinch, a tight jaw, a shrinking in the chair.

These moments are not idiosyncratic. They are shaped by a wider cultural script in which patriarchy organizes who is allowed to feel, who must endure, and who is permitted to hold power. Feminist theory has long articulated this through the claim that "the personal is political" (Hanisch, 1969). In psychotherapy, that claim must be operationalized.

From a Transactional Analysis (TA) perspective, gendered rules and expectations are carried in ego states, transmitted through the Parent, embedded in script decisions, and enacted in everyday transactions (Berne, 1950, 1961). Yet, gendered trauma is not an individual aberration; it is the imprint of law, religion, and cultural norms on power, care, emotional labor, safety, and entitlement across generations and we refer to this as ‘Patriarchy’

Global trends show both the persistence and adaptation of misogyny. Femicide refers to the killing of women because they are women; feminicide names the broader system that enables those killings, encompassing state complicity, impunity, and structural misogyny. Today, this violence is amplified through digital platforms, humanitarian crises, and political spaces, reflecting a backlash to women’s visibility and autonomy.

Nearly one in three women worldwide—around 840 million—have experienced intimate partner violence or non-partner sexual violence, a prevalence that has changed little in two decades (UN Women, 2025; World Health Organization, 2025). This lack of progress underscores that gendered violence is structural, not episodic.

Patriarchy also harms men, though not symmetrically. It constrains emotional expression and links worth to dominance and control, often appearing clinically as emotional restriction, shame, or reliance on control as a relational strategy. Acknowledging this clarifies how patriarchy undermines relational capacity across genders while distributing risk and violence unevenly.

For practice, this context matters. Couple and individual work can rest upon unspoken patterns of coercive control, even when abuse is not yet named. Emotional labor disparity is common: women carry responsibility for relational repair, regulation, and harm minimization, alongside trauma responses such as hypervigilance, dissociation, or self-doubt. Patriarchy normalizes male entitlement to care, attention, and compliance, while rewarding female self-silencing as a strategy for survival.

These dynamics form an invisible architecture that, unexamined, can escalate into gaslighting and coercive control. Contemporary definitions of domestic abuse recognize these patterns, and it remains a leading cause of depression in women, strongly associated with anxiety, PTSD, and chronic stress (World Health Organization, 2025).

Framing such presentations as “a couple issue” risks misdiagnosis. When therapy focuses narrowly on communication without analyzing power, fear, and control, it may collude with harm. Traditional TA models often assume good faith, yet gaslighting directly attacks the Adult ego state. Reframing deception as misunderstanding entails a systematic discounting of danger and contamination of Adult functioning. Without an explicit power analysis, therapy risks creating moral equivalence where there is structural domination.

Building on Drego’s Cultural Parent (1983) and Steiner and Wyckoff’s Radical Psychiatry (1975), we introduce the Political Parent within a new Feminist Liberation Model (McCarthy & Rehal, 2026). The Political Parent accounts for dominant ideologies and organizing logics of power, such as racism, sexism, misogyny, ableism, homophobia, and transphobia.

Located explicitly in the Parent ego state, the Political Parent makes visible how male entitlement is normalized, female self-silencing rewarded, and fear reframed as “insecurity.” We are not born patriarchal; patriarchy is learned. Framed positively, we are born with a capacity for equality and mutual recognition—capacities a feminist Adult can reclaim.

The model supports Adult Decontamination (Berne, 1961) and Child Deconfusion (Goulding & Goulding, 1979; Schiff et al., 1975), enabling a "depatriarchalization" (McCarthy & Rehal, 2026) and decolonization of the Self. The Political Parent functions much like a cultic system, demanding compliance and suppressing critical thought. As Adult capacity strengthens, the Child no longer needs to organize around fear or hypervigilance.

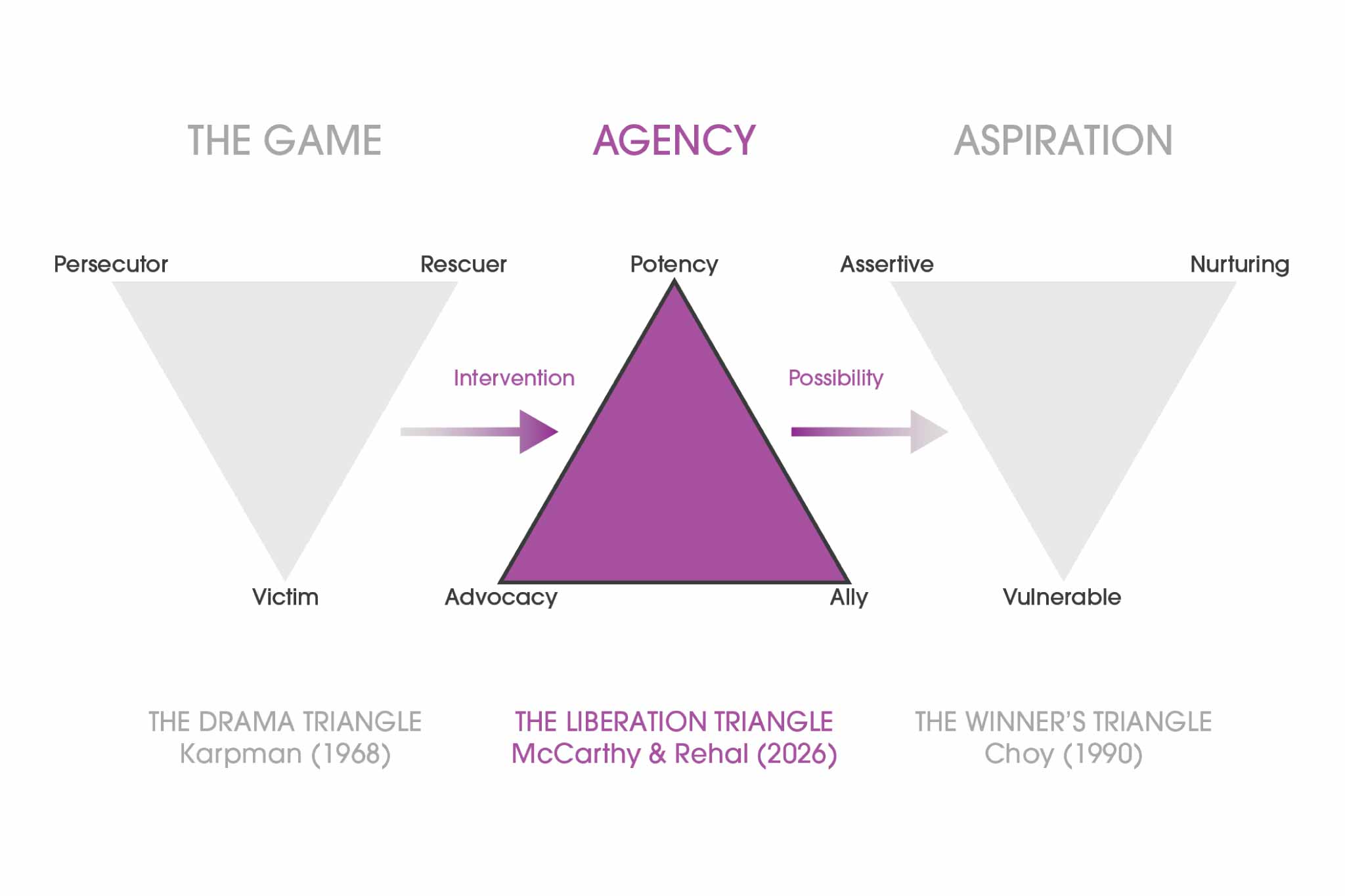

TA’s Drama Triangle illuminates repetitive roles—Victim, Rescuer, Persecutor—but, without a power analysis, can individualize harm (Karpman, 1968). The Winner's Triangle offers healthier positions but may be unsafe for clients living with coercive control (Choy, 1990).

The Liberation Triangle functions as a developmental bridge between the Drama and Winner’s Triangles (McCarthy & Rehal, 2026). It supports movement out of threat-based, asymmetrical dynamics without presuming safety or mutuality. Potency restores internal capacity and choice without pressure to act; Ally positions the therapist in explicit support of safety, reality, and paced work; and advocacy represents the capacity to speak for oneself and set healthy boundaries. Together, these positions restore Adult functioning while actively challenging Political Parent scripts that normalise domination, endurance, and self-silencing, creating the conditions under which Winner’s positions may later become viable.

Patriarchy enters the therapy room whether we name it or not. It lives in scripts, ego states, coercive control, and cultural backlash. The ethical task is not neutrality but clarity. A feminist TA lens is emancipatory: it works to identify the Political Parent, build Adult capacity, and restore the Child from confusion to safety. The models we choose shape what we see, what we name, and whose reality we protect.

Berne, E. (1958). Transactional analysis: A new and effective method of group therapy. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 12(4), 735–743.

Berne, E. (1961). Transactional analysis in psychotherapy: A systematic individual and social psychiatry. Grove Press.

Choy, A. (1990). The winner’s triangle. Transactional Analysis Journal, 20(1), 40–46.

Drego, P. (1983). The cultural Parent. Transactional Analysis Journal, 13(3), 224–227.

Goulding, R. L., & Goulding, M. E. (1979). Changing lives through redecision therapy. Grove Press.

Hanisch, C. (1969). The personal is political. In Notes from the second year: Women’s liberation (pp. 76–78). Radical Feminism.

Karpman, S. B. (1968). Fairy tales and script drama analysis. Transactional Analysis Bulletin, 7(26), 39–43.

Schiff, J. L., Schiff, A. W., Mellor, K., Schiff, E., Schiff, S., Richman, D., Fishman, J., Momb, D., Wolz, L., & Hine, J. (1975). The Cathexis reader: Transactional analysis treatment of psychosis. Harper & Row.

Steiner, C. M., & Wyckoff, H. (Eds.). (1975). Readings in radical psychiatry. Grove Press.

UN Women. (2025). Facts and figures: Ending violence against women. Retrieved January 27, 2026, from https://knowledge.unwomen.org

World Health Organization. (2025). Violence against women prevalence estimates, 2023.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.