The only constant in life is change. However, one of the most common—though often unrecognized—experiences that follows change is grief. In this sense, it is fair to say we are all grieving to some extent, in small and ordinary ways.

Life continuously asks us to meet and let in, or to lose and let go—of people, roles, routines, opportunities, ideas, and familiar ways of being. Some of these changes are dramatic, others barely noticeable. Yet, each one gently reshapes our inner world and our relationship with ourselves and life. Even positive changes can bring experiences of grief because any change touches something fundamental in our world: the basic dimensions through which we relate to others and to life itself.

Modern neuroscience shows that there are three main domains through which we form any relationship: time, place, and attachment. These domains are deeply interconnected and woven into one another, not only in an abstract sense. The neurons and neural circuits related to these experiences are physically located within the same brain area, specifically the inferior parietal lobule (O’Connor et al., 2008).

This is also why grieving is so difficult and takes time. To move through grief, we are required to disentangle changes in time, place, and attachment simultaneously.

With all the change happening in the world and in everyday life, each of us is likely grieving something. If you pause for a moment and look around, you may easily notice things that have changed—sometimes subtly—and that evoke feelings even if you cannot immediately name them. The fact that you are reading this text online is, in itself, a change.

No matter how minor or pleasant a change may be, it still challenges the established order of things. Even changes that bring clear advantages can evoke mixed reactions: a sense of increased access and opportunity alongside feelings of being overwhelmed, pressure to keep up, or the loss of familiar rituals and sensory experiences. What appears externally as progress may internally require adjustment, saying goodbye to some things, and reorganization.

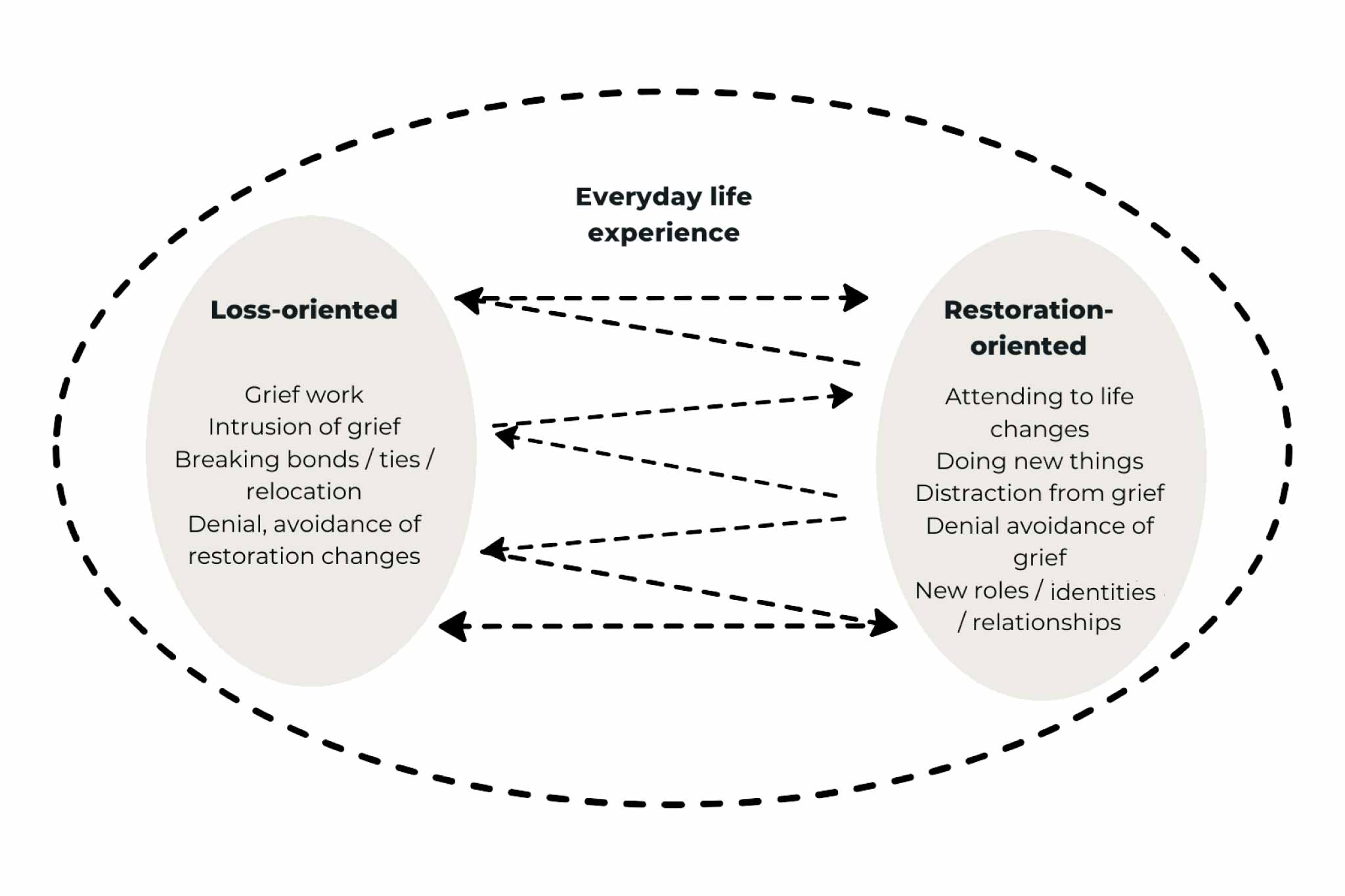

These reactions are natural, and the Dual Process Model of grief describes them well (Stroebe & Schut, 1999). Every change divides our experience into two processes: one oriented toward grief, and the other toward coping (Figure 1).

At one moment, we may be noticing and processing the loss—feeling sadness, confusion, or longing. At the next, we may be distracted, engaging with new roles, opportunities, and experiences the change brings. Moving back and forth between these two processes is what supports healing and integration.

Here lies an important insight: every loss and change carries the potential for growth if we are willing to notice it and allow it into our lives. We may hope pain or discomfort will simply fade with time, but this is not how grief works. As Tonkin (1996) suggests, we do not move on from grief; we grow around it. In doing so, we become something new—updated, changed, and previously nonexistent. Everyday changes, both small and large, can be used to personalize, define, and shape our identity.

In 2022, insights from neuroscience further clarified this process by understanding grief as a form of learning (O’Connor & Seeley, 2022). Grieving means learning how to live with change—in other words, teaching the brain to make new predictions. This learning involves several interconnected tasks:

This understanding resonates strongly with Richard Erskine’s ideas in his article “What Do You Say Before You Say Goodbye?” (Erskine, 1998). Erskine emphasizes working with grief through retelling the story of the relationship in the presence of attuned, emotionally involved listening. Indeed, how can our understanding of a relationship—with a person, a role, or even an object—transform unless we understand what it meant to us and how its change affects us now?

From a neuroscientific perspective, this reflective process is at the heart of adaptive grieving. By engaging with feelings of attachment, changes in time and place, and by moving flexibly between loss-oriented and restoration-oriented processes, we learn, integrate, and grow. When aligned with Transactional Analysis (TA) concepts, this approach supports storytelling, emotional processing, meaning-making, and the integration of change across all ego states.

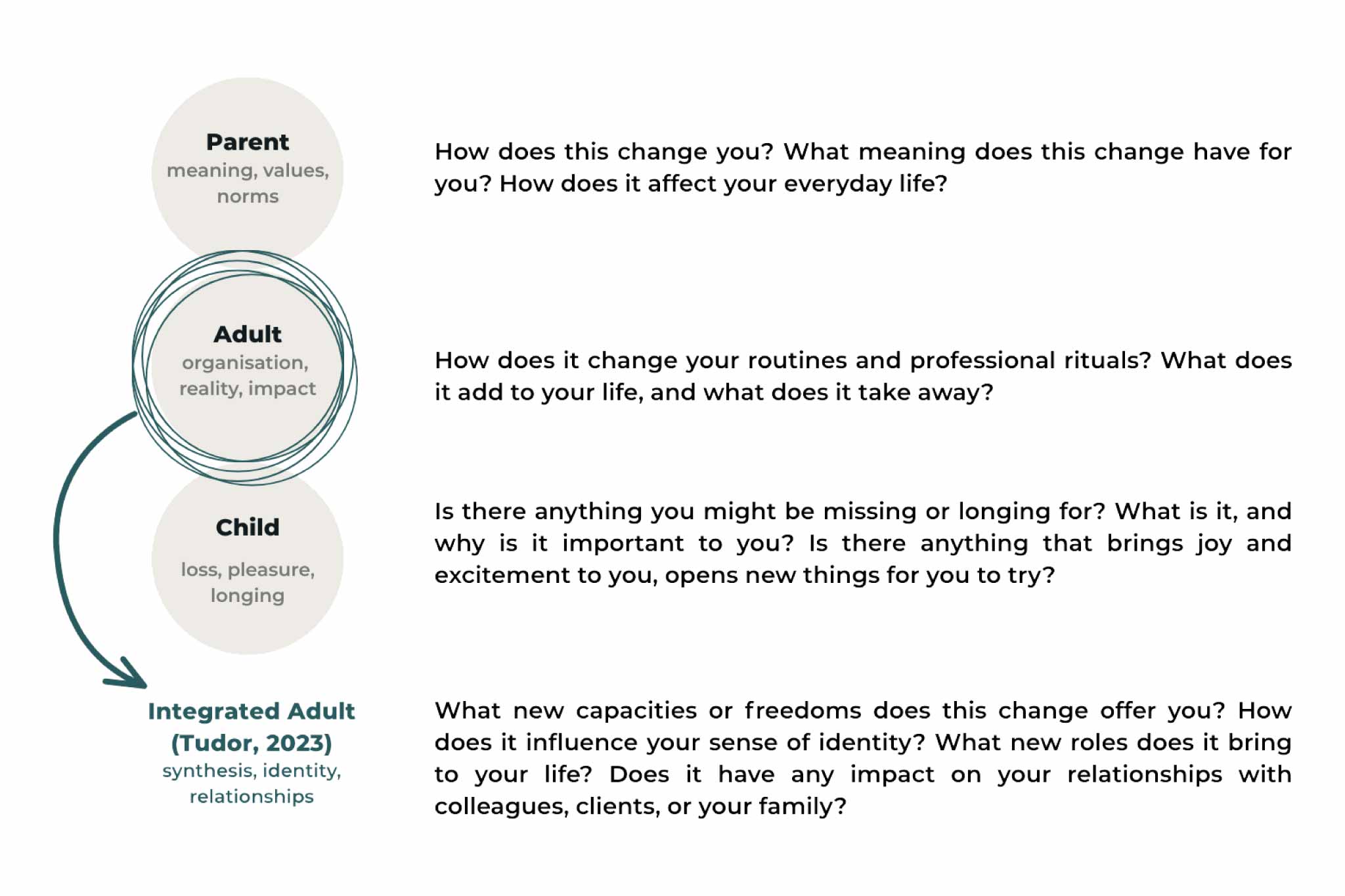

This is where TA can offer a profound and practical perspective on grief, even though grief itself has not been extensively elaborated within TA theory. If we view grief as a form of learning who we are within change, through the lens of ego states, it becomes clear that grief affects all ego states (Berne, 1961). Moreover, any significant change also alters our life roles and identity in broader dimensions.

Let us take the current update—access to the digital version of The Script—as an example of everyday change. We can explore the feelings, thoughts, and potential for growth it may evoke through the lens of TA and recent insights from neuroscience. If you wish, you can pause for a moment and reflect on how this specific change is experienced by you across different ego states. What comes to mind as you gently ask yourself the following questions (Figure 2)?

When we begin to understand grief as an everyday response to change, our relationship with ourselves can soften. Even small shifts may carry both gain and loss: new access and flexibility alongside the change of familiar rituals and sensory experiences. Allowing ourselves to notice these mixed responses helps us stay connected to our feelings, thoughts, and actions, navigating the best way to adapt.

We do not have to choose between appreciation and sadness; they can exist together. In this way, everyday grief becomes part of our ongoing script as a meaningful process through which we learn, integrate change, and quietly grow into who we are becoming.

Berne, E. (1961). Transactional analysis in psychotherapy. Grove Press.

Erskine, R. G. (1998). What do you say before you say goodbye? Transactional Analysis Journal, 28(1), 48–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/036215379802800106

O’Connor, M. F., & Seeley, S. H. (2022). Grieving as a form of learning: Insights from neuroscience applied to grief and loss. Current Opinion in Psychology, 43, 317–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.08.019

O’Connor, M.-F., Wellisch, D. K., Stanton, A. L., Eisenberger, N. I., Irwin, M. R., & Lieberman, M. D. (2008). Craving love? Enduring grief activates brain’s reward center. NeuroImage, 42(2), 969–972. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.04.256

Stroebe, M., & Schut, H. (1999). The dual process model of coping with bereavement: Rationale and description. Death Studies, 23(3), 197–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/074811899201046

Tonkin, L. (1996). Growing around grief. In K. J. Doka (Ed.), Living with grief: After sudden loss (pp. 1–8). Hospice Foundation of America.

Tudor, K. (2003). The integrated Adult ego state. Transactional Analysis Journal, 33(3), 221–231. https://doi.org/10.1177/036215370303300304

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.